In case you're in a hurry, Radu Stern provides a good, International Art English explanation of how these images work right here.

To put other images on his words, let’s take a few examples from the set on this site (and make them chronological by capture date). The reason I’m not going to run through every single picture in the set is to leave open the prospect that the possibility of interpretation is bullshit, tacked on to legitimise the work in the art world. It is important to me that the viewer be able to decide for himself the nature of what he is seeing: not only whether you thinks the work is “good,” but also the nature of the work itself - whether you think it should be considered art, because that is a way of questioning your own definition of art.

IMG_4509 can be read in several different ways.

First, you might read it as a photojournalistic account of the refugee crisis in Southern Iraq that followed the invasion of 2003. Or you might recognise in it a composition that riffs off of a very famous painting - La Liberté guidant le peuple by Eugène Delacroix.

This is intentional, and controlled. While the first layer of interpretation is usually rather understandable, moreso with the assistance of a caption, the second layer is intentionally more cryptic, and often a commentary on the event being depicted, art itself, or both.

Delacroix’s painting is about freedom, and it is about conquering freedom. It uses both elements of allegory and elements of contemporary culture - the central character, which is an allegory of freedom, holds a weapon that is contemporary to the fight that she is leading, opening the possibility that the scene was witnessed by the painter.

The geographical location of this picture is highly charged. Highway 80 was nicknamed the Highway of Death for a good reason. If you have forgotten about it, Ken Jarecke’s Just Another War (which you can get as an ebook here) is an interesting account. Sophie Riestelhueber’s Fait (which Errata has re-edited, you can get it from their website, or from Amazon) is also worth checking out.

Naturally, the only interpretation possible of the Delacroix referent comes within the framework of the history around both Southern Iraq, where the population was, by all accounts, invited to rise up after the 1991 war before being brutally crushed (up to 250’000 Iraqis were killed as a result while the captured weaponry they would have desperately needed to fight back was shipped to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar ) and of the anti-war protests in the buildup to the 2003 invasion.

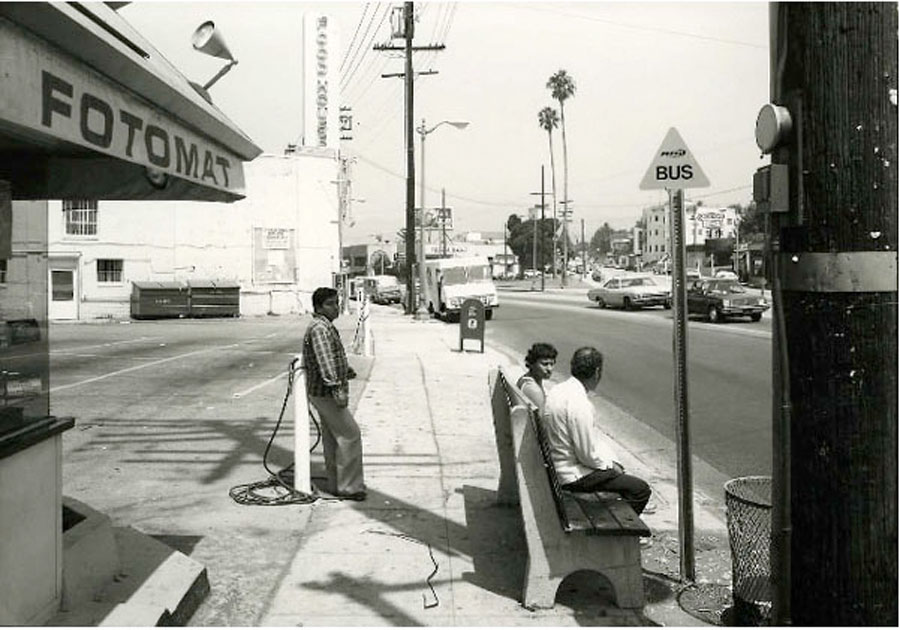

One of the more complex pictures in the set is _MG_1223, as it uses multiple referents, spread over the history of documentary photography. It could, thus, be interpreted as a summary visual representation of the history of the genre.

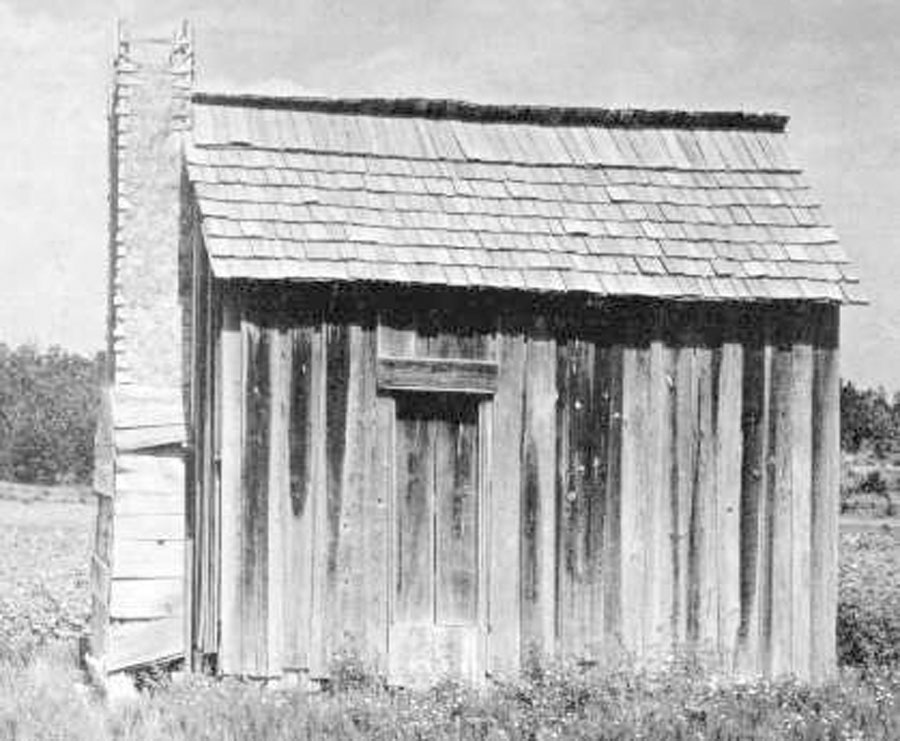

The very left of the image takes from a picture from Walker Evans’ "And let us now praise famous men".

The left of the picture references a picture from Anthony Hernandez’s Bus Stops. Hernandez was linked to a group referred to as the "New Topographics" (named after a landmark show in the 70’s), most notably Lewis Balz.

The center references a Capa picture from the Spanish civil war.

The road references an image from Ristelhueber’s Blow Up series.

The right part of the image references a picture from Gabriele Basilico’s Beirut series

One of the more esoteric referents is probably _MG_8352.

The connotative dimension of it comes from an image in Adrien Cater’s As You Can Clearly See series, which is a meditation on reality in photography, and on the relationship between text and images.

Cater’s piece, Eye Witness, tells the story of Henry Carter, a visitor to Michigan who photographed either a cloud of dust, or a flying saucer flying off in a cloud of dust.